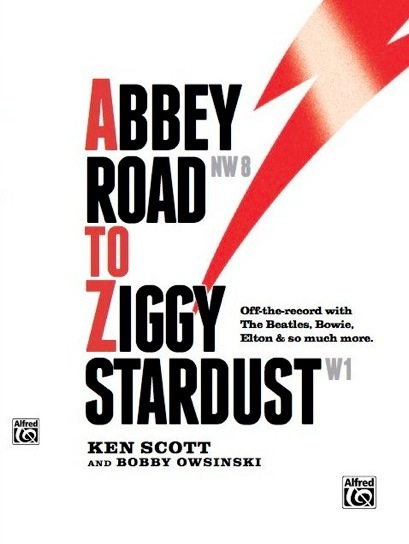

From Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust

The autobiography of legendary producer/engineer Ken Scott.

The book covers:

• Ken’s time at Abbey Road Studios

• Working with The Beatles

• Engineering other EMI artists like Jeff Beck, Pink Floyd, Procal Harem, among others

• Producing David Bowie

• Working with Elton John

• Working with America, Harry Nilsson, The Rolling Stones, and more.

• Managing Missing Persons

• Ken’s time in Los Angeles with Duran Duran and George Harrison

• and much more!

What It's About

Ken Scott holds a unique place in music history as one of only five engineers to have recorded The Beatles. Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust shares the intimate memories of Ken Scott’s days working with some of the most important artists of the 20th century.

Ken’s work has left an indelible mark on hundreds of millions of fans with his skilled contributions to Magical Mystery Tour and The White Album. As producer and/or engineer of six David Bowie albums (including the groundbreaking Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars) as well as other timeless classics, the sound Ken crafted has influenced several generations of music makers that continues to this day. Ken captured the sonic signatures of a who’s-who of classic rock and jazz acts, including Elton John, Supertramp, Pink Floyd, Jeff Beck, Duran Duran, The Rolling Stones, Lou Reed, America, Devo, Kansas, The Tubes, Missing Persons, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Billy Cobham, Dixie Dregs, and Stanley Clarke.

Funny, poignant, and oh, so honest, Ken pulls no punches as he tells it as he saw it, as corroborated by a host of famous and not-so famous guests who were there as well. Plus, you’ll be privy to several exclusive stories, facts, and technical details only available in Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust.

Kind Words From Readers

Ken became a part of that team latterly, which over the years recorded the band to such a high standard – a standard that remains a benchmark today. The work that we did then has stood the test of time and, I think, it will continue to do so. I was lucky to have Ken and the others to assist me during that period of extraordinary creativity. Without them it would have been a different story.

Sir George Martin

I’m still your greatest admirer!

John McLaughlin: Mahavishnu Orchestra

…and dozens more like it!

Let's Look Inside

Table Of Contents

Chapter 1: The Early Years

in this chapter Ken looks at his childhood influences, his penchant for recording at an early age, and the steps leading to his entry into the world of music, thanks to one special girl on the tele.

Chapter 2: Abbey Road

We look at Ken’s arrival at EMI’s Abbey Road Studio and his ascension through the ultimate music recording bootcamp; the EMI training program. Along the way Ken describes the layout of the famed studio, how the training program works, how he barely avoided getting fired (twice), as well as his first meeting and first session with The Beatles.

Chapter 3: Engineering The Beatles

Ken finally becomes a full fledged engineer and his baptism of fire is with, you guessed it, The Fab Four. In this chapter Ken describes working on songs for Magical Mystery Tour and the inside story behind the making of “Hey Jude.â€

Chapter 4: Recording The White Album

Never the ordeal that the press described, Ken takes us behind the scenes during the recording of The White Album and dispels many of the myths about “The Boys†during this period.

Chapter 5: The White Album Epilogue

Faced with a deadline for the first time, Ken outlines the intensity and mad rush to finish The White Album on time. Along the way he lets us in on the never-before-told secrets to songs like “Blackbird,†“Back In The USSR,†and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.â€

Chapter 6: The Boys (And Girls) In And With The Band

After being asked the “What is he really like?†question innumerable times over the years, Ken puts it all on record about The Beatles and the people around them.

Chapter 7: Engineering Other EMI Artists

EMI was more than just The Beatles, and Ken worked with all the artists that came through the studio during that period. In this chapter he relates working with Jeff Beck, Pink Floyd, Procol Harem, among others.

Chapter 8: I Finally Get Fired

Despite having the #1 album in the world, Ken’s relationship with management sours and he’s fired, only to be rehired again. But the writing is on the wall as he develops his exit strategy.

Chapter 9: Trident – My New Home

Ken is hired at Trident Studios, one of the biggest independent studios in London, and immediately begins working with The Beatles again on their various solo projects.

Chapter 10: The Hits Keep Rolling – Or Not

Ken begins to work with some of the cream of the music scene, taking on projects with America, Jeff Beck, Harry Nilsson, The Rolling Stones and Mott The Hoople. Along the way he writes about the Trident studio ghost, the legendary Trident consoles, and the sessions with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young and The Grateful Dead that came close but never came to pass.

Chapter 11: Enter David Bowie

Ken describes his first meeting a none-too-famous David Bowie and his subsequent recording of his Man Of Words, Man Of Music and Man Who Sold The World albums. He then writes about his unforeseen entry into the world of production with Bowie’s Hunky Dory album.

Chapter 12: Elton John

Ken is thrust into the role of mixing Elton’s Madman Across The Water album, then heads to France to recordHonkey Chateau.

Chapter 13: Ziggy Stardust

Even before Hunky Dory is released, Ken and Bowie begin work on Ziggy Stardust. In this chapter Ken describes the making of the album, it’s subsequent success, and Bowie’s rise to stardom.

Chapter 14: Bowie Post Ziggy

With Bowie and the Spiders riding high, Ken works on Lou Reed’s Transformer and his classic “Walk On The Wild Side,†then heads to New York to work on Bowie’s Aladdin Sane. But all is not well as cracks inside the band begin to show.

Chapter 15: The End Of The Team

Bowie disbands the Spiders then heads to France to record Pinups with Ken, but the end of an era seems inevitable. They record the little-seen 1980 Floorshow together, but Ken is left fighting for royalties with Bowie’s management, a battle that will go on for years.

Chapter 16: Elton Take 2

Ken and Elton head to France again to record Don’t Shoot Me, I’m Just The Piano Player, then head to Jamaica for an aborted attempt at recording Goodbye, Yellow Brick Road. While in Jamaica, Ken accidentally finds out why there’s so much bass on reggae records.

Chapter 17: Jazz Fusion

Out of the blue, Ken is asked to leap genres to produce the progressive jazz Mahavishnu Orchestra and what becomes their seminal Birds Of Fire album. His work in the genre continues with Billy Cobham’s Spectrum, but what becomes known as Mahavishnu’s Lost Trident Sessions turn out to be an unpleasant experience.

Chapter 18: All That Jazz II

Ken’s recording technique brings a new kind of sound to progressive jazz, and he continues to work in that area on records with Billy Cobham, more Mahavishnu, and Stanley Clarke.

Chapter 19: Supertramp

Ken initially rejects an offer to work with Supertramp but later reconsiders. Crime of the Century almost never gets off the ground, but after the go-ahead from the record label, it’s decided to make this record as perfect as humanly possible.

Chapter 20: Completing Crime

Ken’s falling out with his management has him leaving the Trident fold, which means that Crime has to be completed elsewhere. The album eventually becomes a break-through hit and a model for future record production

Chapter 21: Crisis, What Crisis?

Ken and Supertramp move to sunny Los Angeles to record the follow-up to Crime, but topping a big hit isn’t always easy as learn to cope with many unforeseen distractions. With Crisis, What Crisis also a success, Ken tries to come to terms with his mysterious breakup with the band.

Chapter 22: Los Angeles

Now permanently an Angeleno, Ken accidentally learns about the world of illegal substances with The Tubes, helps Kansas sort through a new lead singer and a bad contract, and enters the bizarre world of Devo.

Chapter 23: All That Jazz Yet Again

Ken continues to be in demand in the prog-jazz genre as he works on Stanley Clarke’s classic School Daysand watches Stan and Billy Cobham try to outplay one another, mixes one of the first quad albums, and works with a new Jeff Beck.

Chapter 24: The Unspecified Genre

Ken talks about his time working with several bands that defy description; Happy The Man and The Dixie Dregs.

Chapter 25: Missing Persons

Through next door neighbor Frank Zappa, Ken meets the band that becomes Missing Persons. After handling their production, he agrees to professionally stretch out and become their manager.

Chapter 26: Finally, A Record Deal

After a long struggle, Missing Persons finally signs a record deal and has an epic party to celebrate, one that makes the news world-wide for the wrong reason. But the band’s first release, Spring Session M, becomes a hit.

Chapter 27: The Downfall

Ken learns a few painful management lessons, including losing the band for making it look too easy.

Chapter 28: The Downside Of The Business

You win some and you lose some in this business, as Ken records a metal band under extenuating circumstances, does a different kind of production with the funky Level 42, and dabbles in yet again in management.

Chapter 29: Duran Duran

Ken enters the world of superstardom again as he records with Duran Duran and gets a “worst record ever†to go along with his many “bests†along the way.

Chapter 30: George

After 30 years, Ken reconnects with George Harrison to work on rereleasing his catalog. He moves into George’s mansion, goes on a quest for the missing tape, and sees George off one final time.

Chapter 31: The EpiK Epic

The idea for a new kind of drum sound library takes shape as Ken enrolls 5 trusted and talented friends from the past.

Chapter 32: A Look At The Big Picture

Ken answers the questions most asked of him, reminisces on the one project that got away, shares his philosophy on business, recording and life, and sees his perfect final end.

Chapter 19 Excerpt - Supertramp

Supertramp

One way of looking at how I approached Crime was that it started as Google Earth. I knew the overall shape of it, and as we went along it became more like the Street View as we slowly saw every nook and cranny. The fact was that I was actually bored with recording. I’d recorded drums, guitars, tambourines and everything else you can imagine so many bloody times and it was always the same. Since we were going all out on this record, I decided that we should try to make it as different as we can. I threw that concept at the band, and they just ran with the idea.

Like with the sound effects. Most times when sound effects were used on records back then, the engineer would go to the closet that had the sound effects records or tapes, and that’s what he’d use. Everyone used the same ones. I insisted, “If we’re going to do it, we’re going to do it properly and record our own, exactly like a movie,†so we rented a stereo Nagra portable recorder and recorded all of our own sound effects. For example, for the song “Schoolâ€, I went down to a friends house that was two doors down from where my three daughters were going to school, just in time for the lunch break because I knew the kids would be out in the yard playing. I recorded for a half hour, then went off to the studio. Roger would then listen on headphones to try to find bits that might actually work in the song, and we’d go through it and finalize what we were going to use.

For percussion we tried to use different things that weren’t typical percussion instruments. On “Dreamer†there’s a part that under normal circumstances would have been a tambourine, but that would’ve made it so ordinary. In trying to get something different, I had the idea of getting Rick [Davies] to shake a pair of drum brushes. He started off doing it rather heavily, but all you could hear was a whistle from them. We got him to slow it down a bit and do it with more wrist than arm action and suddenly we got the effect that we wanted. There’s a kind of whistle there at the same time as the brushes go through the air, which makes it sound totally different than anything you’d expect but still fills the rhythmic need.

Probably one of the best examples of teamwork was when recording some tom overdubs, also on “Hide In Your Shell.†We wanted to get a change in pitch on each tom hit, so every time Bob [Siebenberg, Supertramp’s drummer] hit a tom I changed the varispeed, speeding the tape up and then bringing it back to normal. When played back this makes the tom’s pitch go down and then as it tails off it goes back up to normal. Bob had to hit the tom on beat with the tempo going all over the place, a feat he accomplished admirably as can be heard on the final product.

Some of the sounds that we got would be done on a synth these days, but synths weren’t around so much back then and we made a conscious effort not to use them if possible. We only used a MiniMoog and an Elka String Ensemble occasionally. For “Dreamer†I had this idea for two sustaining notes, so we decided that I should play it on wine glasses. We got a couple of wine glasses, poured the right amount of water into them to tune them up, then I played them. We recorded the first note, then went back and got the second. By playing wine glasses I mean that I was rubbing my fingers around the top edge, just like those damn annoying kids in restaurants. Everything has it’s use eventually.

On “HIde In Your Shell†I had an idea for a melodic line. Now I can’t say that these type of ideas spew forth from me all the time and that might be a blessing in disguise, as it’s often hard for me to get them across as I’m not a musician. On this occasion I finally managed to get this line idea across to Roger, who worked it out and played it on a keyboard, but it sounded too ordinary. We tried it a couple of other ways and finally, we brought in a guy to play it on a musical saw, which is what you hear on the record. What an amazing sound. So cool that we asked the musical sawist to jam a bit, which we of course recorded as well. Unfortunately I have no idea whatever became of the tape of the jam, but his part on the song worked perfectly.

Probably one of the best examples of teamwork was when recording some tom overdubs, also on “Hide In Your Shell.†We wanted to get a change in pitch on each tom hit, so every time Bob hit a tom I changed the varispeed, speeding the tape up and then bringing it back to normal. When played back this makes the tom’s pitch go down and then as it tails off it goes back up to normal. Bob had to hit the tom on beat with the tempo going all over the place, a feat he accomplished admirably as can be heard on the final product.

Everything but the kitchen sink went into this recording. Actually we got pretty close to a kitchen sink as well. The session percussionist extraordinaire and all around nice guy Ray Cooper had once told me of something which apparently was used a lot in horror movies – a water gong. You take a gong, hit it and then gradually lower it into water. This creates a strange, eery effect because as the gong is immersed the water makes its pitch change. We were working on the ending of “Crime of the Century†and for those that don’t know, “Crime†is in two parts. There’s the song and then it goes into a seemingly endless piano part during which it builds and builds with different instruments and lines coming and going throughout. We were at the point where the drums came in and we needed something to point out that something big was about to happen. Enter the water gong.

Now that name is slightly incorrect because it ended up that we didn’t actually use a gong; we used a piece of sheet metal instead, but it worked just as well. We rented a large fish tank and filled it with water and, at the appropriate time, Bob struck it and lowered it into the water, and it sounded amazing. What’s great is that if you hear it on its own with no other instruments and without any reverb, you actually hear the water bubbling. So cool. That effect actually became a pet thing for me as I used it in one form or another on a number of future albums as well. A word of warning however; the filling of the fish tank is slow but fairly easy to accomplish, one bucket of water at a time. But, once you’ve finished the recording you’re left with one hell of a heavy fish tank to empty and so you have to have a fair number of pretty hefty guys to get it to the kitchen or bathroom sink to empty it.

We were always looking for different things that could be used for percussion. If we saw a cardboard box or a pillow, we’d be hitting it all over to see what it sounded like. It was that kind of thing. I remember walking into the studio very early on in the recording process and I just went all across their wooden floor on my hands and knees with this block of wood, hitting it on the floor in various places to see how the sound changed. I finally found the right spot, which we then recorded. That’s the way we were.

For the instruments, we used the varispeed out-of-tune piano trick that I used with Elton on occasion. We put things through Leslies. On “Hide In A Shell,â€Â for instance, we played a bass note on the MiniMoog through the Leslie so it doesn’t sound like a synth. Anything and everything we could come up with, but the big thing was that we made decisions, quickly and without hesitation. After all, we only had 16 tracks to work with.

We had to have exactly the right sound for exactly the right section. A lot of people might say we went over the top, especially when you consider that on any given song there could be as many as thirty different guitar sounds. Another example; the drum sound that we had for the first half of “Crime†started to sound wrong. We were at Scorpio by this time and we just decided to re-record the drums for the first half of the number. To me, it’s another one of those situations where a unique sound was achieved purely by accident. There was a certain amount of drum leakage into the piano on the original track, and as Bob is a human and not a machine, he didn’t play the part exactly the same way on the overdub, which you can hear. As a result, there is a double-track effect, but as the original kit was in the Trident drum booth and is only picked up through the piano mics, it lacks any kind of presence and gives this almost “am I really hearing a double or is it my imagination†effect.

We went completely overboard on everything, which is why the album took close to six months, a very long time for an album back then. Once we were given that crucial go-ahead from the label, we had no real choice but to strive for perfection.”

Chapter 13 Excerpt - Ziggy Stardust

Ziggy Stardust

Ziggy As A Concept

There’s always been this whole thing about Ziggy being a concept album, but it really wasn’t. There are only two rock albums that I would 100% consider concept albums; Tommy and Quadrophenia by The Who, and that’s because they were written as a complete piece, whereas Ziggy was just a patchwork of songs. Yes, they fit together very well and one can weave a story from some of them, but when you consider that “Round and Round†was originally there in place of “Starman,†it doesn’t make much sense as a concept. How does “Round and Round†ever fit into the Ziggy story? It’s a classic Chuck Berry song. How does “It Ain’t Easy†fit in with the Ziggy concept? That was taken from the Hunky Dory sessions. All this about Ziggy being Starman is bullshit. It was a song that was just put in as a single at the last minute at the record label’s insistence. So while it’s true that there were a few songs that fitted the â€conceptâ€, the rest were just songs that all worked well together as they would in any good album.

Even David didn’t take the Ziggy concept too seriously at first (that would come later). He has told various stories of how the character came into existence. Supposedly, in one tale, the name Ziggy came from a London tailor shop (“Ziggy’s”) that David had seen from the train, and in a later version he told Rolling Stone that Ziggy “was one of the few Christian names I could find beginning with the letter Z.†David has also been quoted in many interviews stating that the character Ziggy Stardust was based upon the Elvis impersonator Vince Taylor, an eccentric leather-clad Brit who achieved a level of stardom in England in the late 50’s before having a very public mental breakdown and winding up in a psychiatric institution. And just as an aside, many, like the Clash’s illustrious Joe Strummer, even considered the bizarre Mr. Taylor to be the beginning of British rock and roll.

“I met (Vince Taylor) a few times in the mid-Sixties and I went to a few parties with him. He was out of his gourd. Totally flipped. The guy was not playing with a full deck at all. He used to carry maps of Europe around with him, and I remember him opening a map outside Charing Cross tube station, putting it on the pavement and kneeling down with a magnifying glass. He pointed out all the sites where UFOs were going to land.”

Bowie, from Golden Years; the David Bowie Story on BBC Radio 2, 18 March 2000

But as David and the band hit the stage after the album was complete, David began to become the Ziggy character and the the public ate it up.

Ziggy Hits The Charts

There’s a conversation I’ve had twice with the acts I was working with. Once when we were close to the end ofZiggy and the other was during the recording of Supertramp’s Crime of the Century. Basically we thought both of those albums would be successful in America but not as much in England. What gave us the opinion they were more US oriented I have no idea, but that’s the way we felt. On both occasions it turned out to be the complete opposite. For both acts it took 5 years to happen in America, and in the meantime they had #1’s throughout the world.

Hunky Dory came out on December 17, 1971 in the UK, almost immediately after we finished recording Ziggy, and didn’t make a huge splash. It did give David more notoriety and allowed him to begin to build a following through touring, but everything changed with the release of Ziggy Stardust on 6 June 1972.

The record blew up in the UK immediately, eventually reaching #5 on the UK charts, but only #75 on the Billboard 200 a full year later. The single, “Starman,†reached #10 in the UK, but again, only #65 in the US. A second single off the record, “Rock n’ Roll Suicide,†reached #22 in 1974. David had now become a full-fledged cultural phenomena in England and other parts of the world, as Ziggy, with The Spiders From Mars, played to sold out concerts in the UK, Japan, and a few parts of the US.

One of the byproducts of a hit record is that it lifts the sales of the entire catalog, and Bowie was no exception, as Hunky Dory entered the charts in September, two months after Ziggy was released. Eventually the album would hit #3 and have a chart run for over a year. “Life On Mars†was released as a single and also soared to #3. “Changes†was released three years later and reached #1. Still, both albums only slightly dented the US charts, even with pockets of success in the larger cities of the north and west, but five years later, America finally got the Bowie fever. There were small areas where Ziggy did really well, but it was mostly underground in the rest of the country. Of course, David’s whole androgynous image was way too much for many people to handle, especially in the deep south, and I seem to remember a story about them having to run for their lives at a roadside cafe when they were touring down there.

So how did I hear about David’s success? I was sitting in the reception area at Trident reading the paper when Gus Dudgeon walked in and congratulated me. Surprised, I asked, “What for?†“Ziggy entered the charts this week at #7!,†he exclaimed. That was how I learned it was a hit. My feeling, although I have no direct evidence, is that the record was bought into the charts because that’s the kind of thing that David’s manager, DeFries, would do, and at that particular time in England it wasn’t that difficult to do, or that unusual. In fact, there was a story that the whole Virgin chain was built around a company’s ability to buy records in. Supposedly Richard Branson set up just enough stores in key places so you only had to go to his stores to buy a record into the charts. Management or labels would give students the money to go buy the record from Virgin stores which created just enough sales around the country to register it as a hit. If the story is true I can say nothing other than……“Brilliant!â€

“I actually always thought it was because we did The Old Grey Whistle Test. We did a TV show up in Manchester in which we did “Starman†on that, which reached a lot of the kids. Then we did the Old Grey Whistle Test that reached a lot of the hippie crowd, and it took off after that. We played a club and DeFries was all excited because he managed to get Mike Moran down from Top Of The Pops to come and see us. And it worked. I think we played Top Of The Pops even before “Starman†had charted.”

Trevor

Although success seems to be a wonderful thing, it frequently doesn’t play out the way you’d think. Right after Ziggy became a success, all kinds of unfortunate legal things around David started to transpire – everything from Trident not having their bills paid to me not receiving any royalties. At that point it became common knowledge that DeFries had split from Gem Toby, set up his own company (Main Man) and took Bowie, and others, with him. From then on, there were lots of law suits all around that wouldn’t stop for many, many years.

I have to pass comment on how amazed I am that forty years after we recorded Ziggy we’re still bloody talking about it. It was never meant that way when we originally did it because back then we thought that an album would have a six-month life span. We had no idea that all these years down the line people would still be interested. Rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t even that old at that point, so how could anyone know?

Chapter 3 Excerpt - Engineering The Beatles

Engineering The Beatles

“I Am The Walrusâ€

The next session that I remember was my first orchestral date three days later and it happened to be for “I Am The Walrus,†a song that I would later mix as well. The basic track and vocal had already been recorded by Ernie, so the session I worked on added the orchestra, the choir, and maybe a few other things that I can’t remember because, once again, I was thrown into the fire and scared to death.

As Geoff was the one that I was following, I started off with the same setup and mics that he had used, just the same way he did when he followed Norman Smith or Malcolm Addey when he started. You saw how those before you had done it and just tried to replicate everything as best as you could. Slowly but surely you could start experimenting a little once you got a grasp of things, but this was way before I reached that point.

Surprisingly, I learned something from those sessions that later became invaluable to me as a producer. I discovered that the best way to work with an orchestra is to have the arranger overwrite. The reason is that it’s always easier to get rid of material than to put something in during a session. That’s what George Martin used to do on his arrangements for Beatle songs, and that’s what he did on “Walrus.†The first hour of the session was John saying, “I don’t like that bit. Keep this bit. Can you change that a little?†George made the changes and then we recorded it.

Later when it was time to mix “I Am The Walrus,†John decided that something else was needed for the ending of the song, so Ringo was dispatched to a corner of the control room with a radio tuner to scan around the dial to different stations. What was tricky was that since we didn’t have any extra tracks to record it on, he had to perform the radio tuning live as the song was mixed. On one pass he hit on a performance of Shakespeare’s King Lear on the BBC’s Third Programme, which we all determined worked perfectly for the track. We kept the end of that take and decided to use another mix for the first part of the song.

I was asked to do an edit between takes to marry the good ending with a better front half of the song. Now EMI engineers were not supposed to take a razor blade to the tape because, as explained previously, the studio employed a team of dedicated editors. But when you’re working with The Beatles and they want to hear the first half of one mix and the second half of another, you can’t wait until the next day for the editors to arrive. Even though I was used to banding, this was one of my first real actual edits, so once again I was gripped by fear. As I was rocking the tape backwards and forwards to try and find the edit point everyone seemed to be talking at once at the top of their voices, and I couldn’t hear a damned thing. At some point I lost it and screamed in a panic, “Please, shut up. I’m trying to do this!†Much to my surprise, everything immediately fell quiet, which might have been even worse because now the spotlight was directed squarely on me. “Can I cut this without spilling any of my own blood on a precious Beatles master?â€, I wondered. Luckily when I played it, all sounded fine and everyone was pleased, especially me. Dodged yet another bullet.

The mix of “Walrus†that we did that night was mono, and it wasn’t until later that Geoff [Emerick] remixed it in stereo. If you listen to the end of the stereo mix where the radio comes in, it suddenly changes to fake stereo with the bass on one side and the treble on the other. This was because the part with the radio was done live as part of the mono mix and there was no other way to recreate it in stereo at the time. Later when it came time to do the Love soundtrack, it had been discovered exactly which broadcast it was that Ringo had tuned into, and the BBC made it available so it could finally be recreated in proper stereo and 5.1.